US$57 billion of Belt and Road Initiative funding is set to help remedy Pakistan's chronic energy shortages.

The selection of Karachi, Pakistan's largest city, as the location for the 17th World Wind Energy Conference and Exhibition (held earlier this month) was far from random. Over recent years, Pakistan has invested heavily in wind-power, while also enlisting Chinese backing, under the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) framework, in order to bring its new environmentally-friendly facilities online.

As a result, in September 2017, the country's National Electric Power Regulatory Authority announced that the share of wind power in the nation's overall energy mix had increased by 0.46% to 1.23%. This has ensured that the country is well on track to meet its 2030 target of having 5% of its overall electricity derived from wind-power, a goal set back in 2006.

Pakistan's ambitious energy-development program has been driven by its long-overdue need to address its chronic electricity shortfall. Although the bulk of its enhanced supply is expected to be derived from domestic coal reserves, the development of wind, solar and hydro sources has also been prioritised in recent years. This has been spurred by growing environmental awareness in the country and, crucially, a steady fall in the cost of renewable-energy generation.

The first commercial wind project in the country came online in 2009 as part of the initial development phase of the Jhimpir Wind Power Plant. The project was overseen and managed by Zorlu Energy Pakistan, a subsidiary of Turkey's Zorlu Enerji. With additional wind turbines coming into operation, the plant's capacity reached 56.4MW in July 2013, all of which was fed into the country's national grid.

To date, though, this is a seen as only scratching the surface in terms of what could ultimately be delivered. Set in the Gharo-Jhimpir Wind Corridor, a 180km strip of coastal land, the Pakistan Meteorological Department sees the facility as having the potential to produce up to 11,000MW of wind-derived electricity.

Following the success of this first plant, a number of additional wind-power projects were swiftly commissioned. By the end of 2015, according to the Alternate Energy Development Board (AEDB), the Pakistani government's renewable-energy agency, there were more than 40 wind-energy projects under development across the country. Once online, they are expected to contribute about 2,050MW to the national grid. By mid-2017, 13 such projects had become operational, representing a net grid contribution of 200MW.

Subsequently, once the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) – one of the key BRI conduits – was established, some US$57 billion of mainland funding was earmarked for investing in the development of Pakistan's infrastructure, with much of this allocated to energy-related projects. Of these, four wind-farm investments were prioritised – Sapphire Wind Power Plant, Sachal Wind Farm, Dawood Wind Farm and Jhimpir Wind Farm.

The first of these to be completed was the 52.8MW Sapphire Wind Power Plant, which became operational at the end of November 2015. Beijing-headquartered HydroChina, a subsidiary of the Power Construction Corporation of China, was the lead contractor on the project, its first such installation in Pakistan.

The company also took the lead on the 50MW Sachal Wind Farm, which came online in April 2017 and is, again, based in the Jhimpir Wind Corridor. The farm is owned by Sachal Energy, a wholly-owned subsidiary of the Arif Habib Corporation, one of Pakistan's leading investment groups. Debt financing was provided by the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC) and the estimated cost of the project was $134 million.

The third priority project, the 50MW Dawood Wind Farm, was developed on tidal flats near the city of Banbhore, about 80km east of Karachi. Also coming online last April, the project was backed by a $78.8 million ICBC credit line, while its turbines came courtesy of Guangdong's China Ming Yang Wind Power Group in association with Aerodyn Energiesysteme, a German wind-power specialist. The final project – the UEP 100MW Jhimpir Wind Farm – was also developed by HydroChina. Following investment of about $250 million, it became operational in June last year.

At present, there are nine more Chinese-backed wind-power projects at various stages of completion across Pakistan. Once operational, they will feed an additional 445MW into the country's national grid.

Geoff de Freitas, Special Correspondent, Karachi

Editor's picks

Trending articles

Belarus, a landlocked nation in Eastern Europe bordering Russia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland and Ukraine, has caught rising interest among Hong Kong’s business community in recent years under the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Going hand in hand with its role as a transport gateway linking China with the EU and CIS countries, it is seen as an increasingly open investment destination for manufacturing and high-tech developments.

An Important Transport Node on the Silk Road Economic Belt

Strategically located on the new Eurasia land bridge, eight rail container routes on the China-Western Europe trade pass through Belarus, enabling cargo to move much faster between China and Germany via Kazakhstan, Russia, Belarus and Poland, taking about 17 days. In comparison, sea freight takes around three weeks longer, although the freight cost of travelling by rail is about 60-70% higher. As shippers have become more receptive to the expanding rail container routes, more than 3,000 Sino-European trains used Belarus’s rail network in 2017.

Source: Great Stone Industrial Park

Two pan-European Corridors – II (Berlin-Moscow) and IX (Helsinki-Greece) – pass through Belarus, strengthening its position as a main trade and transport thoroughfare in the region. Standing at the border between Belarus and Poland is the Kozlovichi-Kukuryki checkpoint – one of the busiest cargo truck checkpoints between the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) and the European Union (EU).

In light of the recent enlargement of Poland’s Pomeranian Special Economic Zone (PSEZ) with an aim of integrating with the New Silk Road Route connecting China and West Europe near the Polish-Belarusian border and the ongoing talks with Germany’s Duisburg Inland Port about the Duisburg-Brest-Minsk rail link, cross-border traffic between Poland and Belarus is expected to soar in coming years.

To cope with the expected traffic growth, the country is continuing to upgrade or convert cities such as Brest and Grodno into large trans-shipment centres and logistics hubs. While the details of the project have not yet been disclosed, it has been reported that the China Gansu International Corporation for Economic and Technical Co-operation (CGICOP) is about to start construction of its own transport and logistics complex in the Grodno region, close to the cargo-and-passenger border crossing point between Belarus and Poland.

Currently, more than 100mn tons of goods transit through Belarus every year, supporting a large transport sector that accounts for 6% of GDP. The present volume of trade, as well as the country’s ongoing investment in infrastructure for transportation and manufacturing industry, continues to make Belarus prosper as an important node on the Silk Road Economic Belt.

Having reaped the early profits from the increasing level of Asia-Europe rail traffic, the country’s state-owned railway company, Belarusian Railways, is anticipating an uptrend in Eurasian cargo flows. For 2018, it expects container shipping on the China-EU-China route to grow by a further 30% to top 300,000 containers, after a 74% year-on-year growth to 245,400 containers last year.

As new logistics and trans-shipment facilities are being built to handle the switches between broad-gauge (1,520mm) and standard-gauge (1,435mm) rail for trains carrying Chinese/Asian cargo to the EU market, or consolidate shipments before sorting and sending to final customers or warehouses in Europe, industry agglomeration featuring manufacturing relocation is also in the offing.

A Manufacturing Relocation Destination

Under Belarus’s membership of the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU or EEU), products made in Belarus can be treated, subject to the country of origin rules, as Belarusian-made and able to be exported to the other EAEU markets of Russia, Kazakhstan, Armenia and Kyrgyzstan, free of tariffs.[1] This, coupled to the country’s geographical proximity to most of the markets in Europe, as well as well-connected road and rail transportation networks, helps to make Belarus an attractive destination for foreign manufacturing companies.

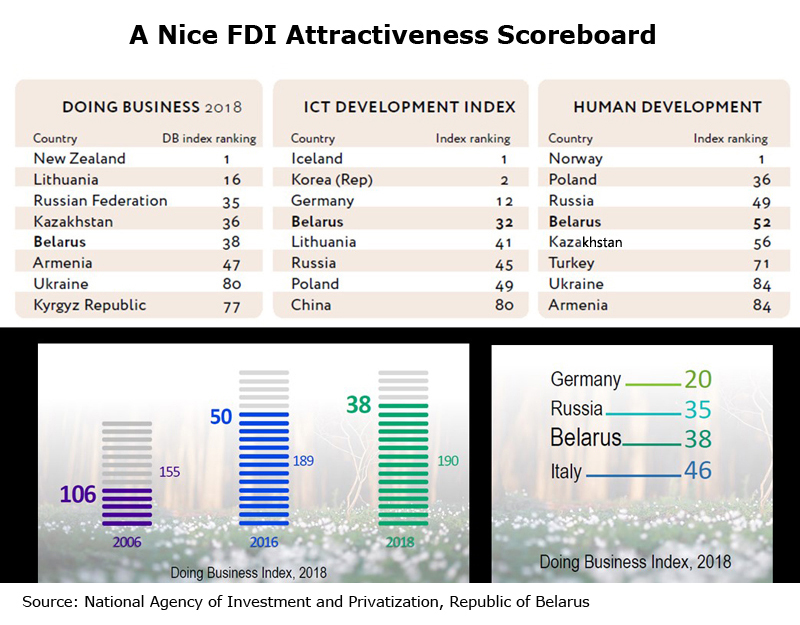

Source: National Agency of Investment and Privatization, Republic of Belarus

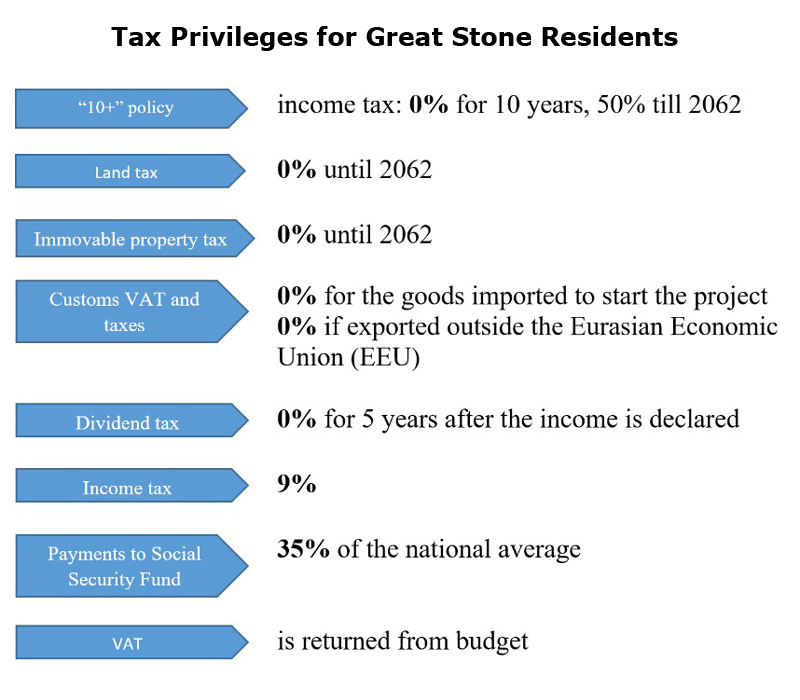

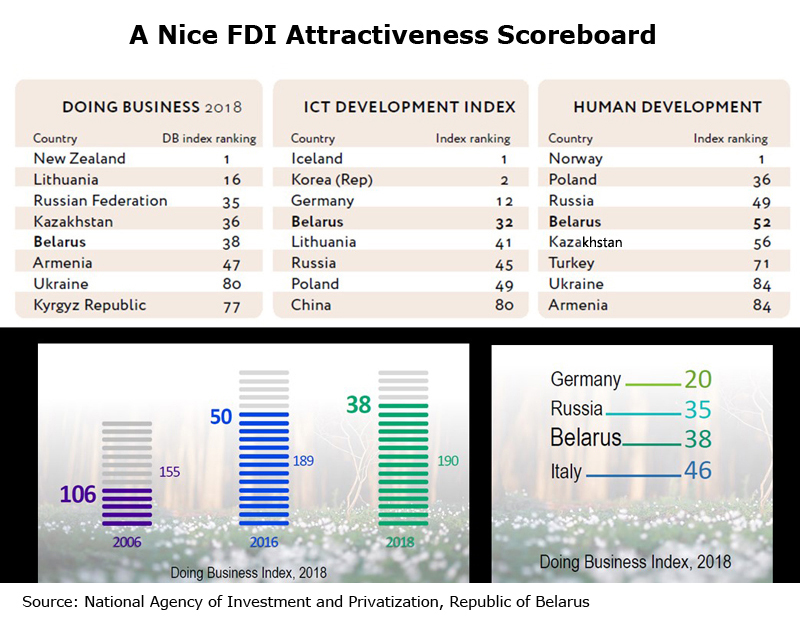

To oil the wheels further, the Belarusian government has continued to liberalise its economy and provide generous investment incentives. As a result, it has welcomed increasing numbers of foreign investors in a number of priority sectors that feature export-oriented, import-substituting and high-tech industries, such as information and communication technologies (ICT), creation and development of logistics systems, home appliances and electronics and the production of electrical equipment.

As an added incentive for new-to-the-market companies, the Belarusian government has established six free economic zones (FEZs) across the country’s six major regions – Brest, Gomel, Grodno, Minsk, Mogilev and Vitebsk. All of these offer would-be investors a range of incentives, including preferential arrangements on corporate income, real estate and land taxes.

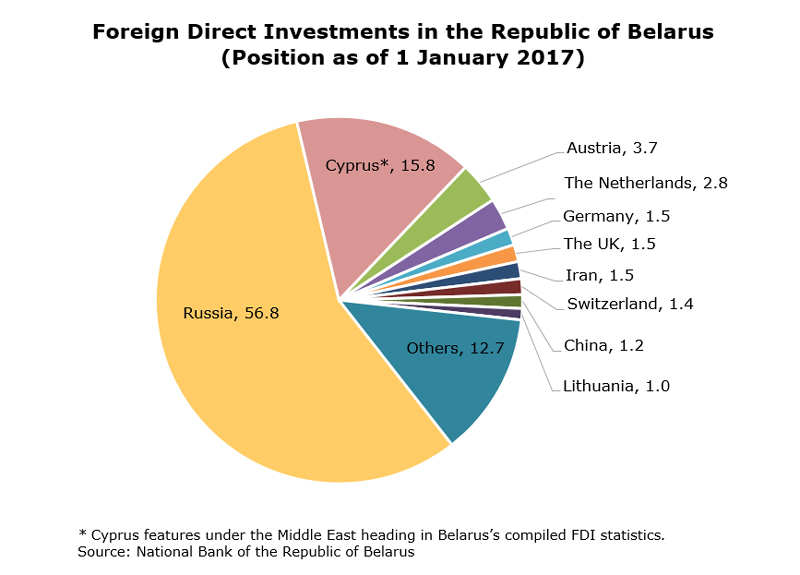

Chinese investment, which grew more than 11-fold between 2011 (US$19mn) and 2017 (US$232mn), is one of the factors spearheading the manufacturing investment in Belarus. Most notable examples of Chinese investment in Belarus include Midea Group’s joint venture with Belarus’ Horizont Holding Company, which has been producing microwave ovens and water heaters in the Free Economic Zone Minsk (FEZ Minsk) on the outskirts of Minsk since 2007, and the China-Belarus Industrial Park, otherwise known as Great Stone Industrial Park, which was co-founded by Hong Kong-based state enterprise China Merchants Group (CMG) in 2012 and is expected to operate until 2062.

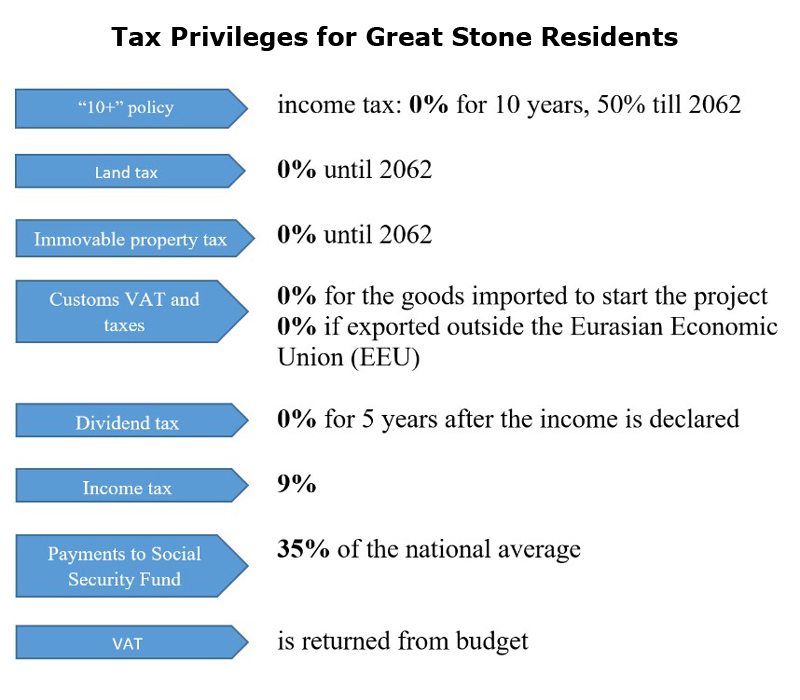

Thanks to its unrivalled perks, such as exemptions on corporate income tax, value-added tax (VAT), VAT on imports, real estate tax, land tax and tax on dividends, Great Stone has had great success in attracting Chinese companies. Current residents include ZTE, Huawei, Zoomlion, YTO Group Corporation, Xinzhu Corporation, Lotusland Renewable Energy and CGICOP. Other deals in the pipeline include companies working in the fields of composite materials, film coating technologies for cars, and joint design.

Source: Great Stone Industrial Park

With Phase I of the park’s development now completed, the Great Stone Industrial Park expects to see the number of resident companies grow from the current 27 to at least 35 by the end of 2018, when Phase II is due to finish, and to 60-70 by 2020 under Phase III of the development.

To facilitate Sino-European cargo flows, Great Stone has been holding talks with Germany’s Duisburg Inland Port about linking up to the Duisburg-Brest-Minsk rail service, and there are plans for a direct connection between the park and Minsk International Airport, 5km away. This should help the park further develop multimodal logistics involving air-rail and/or air-road freight.

An Evolving High-Tech Economy

Also in sync with the country’s development vision is the advancement of the high-tech industries. Few people know that Belarus has had a strong industrial base since the Soviet era, with a world class reputation for the quality of its machinery manufacturing, chemical engineering, petrochemicals, light industry (e.g. textiles, knitting, sewing, footwear, and household electrical appliances) and food processing.

Belarusian companies that have achieved international success include Polimaster, which makes radiation detection equipment and is said to have 20% of the US market in radiation measurement devices; Belshina, producer of some of the largest tyres in the world; and BelAZ, manufacturer of the world’s most powerful dump trucks with a capacity of 496 tons. The country is also a leading manufacturer of potash fertiliser, with an estimated one-sixth of the global potassium market.

Source: National Agency of Investment and Privatization, Republic of Belarus

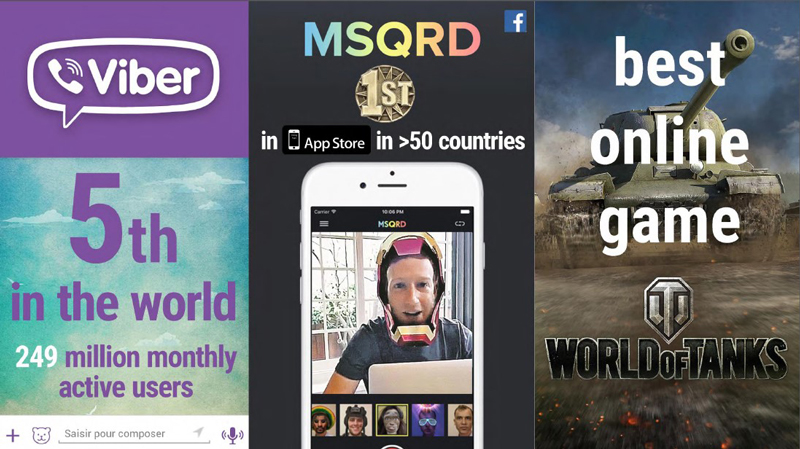

To counter its lack of natural resources, the country has built on this robust industrial foundation by establishing a reputation for technological innovation and nurturing the rapid growth of its IT sector. Between 2006 and 2016, Belarus’s export of IT services grew at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 35% from US$48mn to US$957mn. The sector’s share of Belarusian exports grew from 2% to 14% over that period.

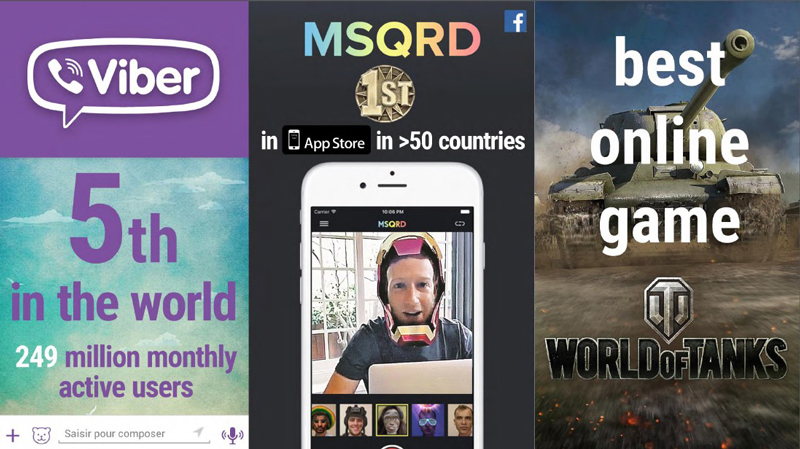

Successful Belarusian IT products include Viber (one of the world’s most popular cross-platform instant messaging and VoIP applications, with much of the development outsourced to Belarus), Viber, face-swapping application, MSQRD and multiplayer online game, World of Tanks.

Source: National Agency of Investment and Privatization, Republic of Belarus

Many of Belarus’s more pioneering tech companies are keen to tap into the opportunities offered by China and other countries across Asia, and see Hong Kong businesses as their natural partners in any such move. Furthermore, as an acknowledged IP hub, Hong Kong is uniquely positioned to help Belarusian tech companies fulfil their technology transfer aspirations and successfully commercialise their IP properties in the wider Asian market.

To oil the wheels of economic upgrade and diversification, Belarus has been understandably keen to attract overseas investment in recent years, while also being open to privatising a number of its state-owned industries. It has launched a series of economic reforms, including the Presidential Decree No. 8 “On the Development of Digital Economy” which allows cryptocurrency-related companies to operate and create crypto platform operators and cryptocurrency exchange operators in the country’s dedicated High-Tech Park (HTP).

Initiatives like these are designed to upgrade and diversify the Belarusian economy from its Soviet-era reliance on heavy machine-based industry and agriculture. The idea is to encourage the engagement with the high-tech sector, in particular with blockchain technology, cryptocurrencies and self-driving vehicles. It’s hoped this will make the country much more competitive in the modern digital economy and create the conditions to attract global IT companies to Belarus.

Belarus, which has one of the lowest rates of corruption among the ex-Soviet states, has also been increasing its efforts to liberalise the economy and improve its business and investment environment. One recent measure along these lines was a presidential decree issued by Alexander Lukashenko to minimise the state’s interference in commercial operations.

This continued liberalisation, coupled with a stable government, is clearly contributing to Belarus’s encouraging recent improvement on the various scoreboards measuring levels of competitiveness and the ease of doing business. This is likely to continue, with the plan to kick-start a new wave of privatisation, which will see four state-owned/controlled companies – OJSC Kryon (which makes air separation products), OJSC Lakokraska (paint and varnish materials), OJSC 8 Marta (linen, knitwear and hosiery) and OJSC Lenta (home textiles, technical/industrial/medical materials) – being sold off.

In a further bid to promote investment opportunities within the country, in February 2017, the Belarusian government granted five-day visa-free travel to citizens of some 80 countries and territories. It is currently considering granting 30-day visa-free entry to Chinese citizens.

As a key element in facilitating greater synergy between Hong Kong and Belarus, HKSAR passport holders have been entitled to visit Belarus visa-free for up to 14 days since 13 February 2018[2], following the formal adoption of a Comprehensive Agreement for the Avoidance of Double Taxation (CDTA) between the two parties on 30 November 2017.

A New Level of Sino-Belarusian Co-operation and Hong Kong Opportunities

Belarus, an active BRI participant, is offering a slew of lucrative business possibilities for Hong Kong and mainland entrepreneurs. Merchandise trade and manufacturing production aside, evolving promises on infrastructure investment are poised to bring Sino-Belarusian co-operation to a new level and give Hong Kong’s professional services providers a new world of opportunities.

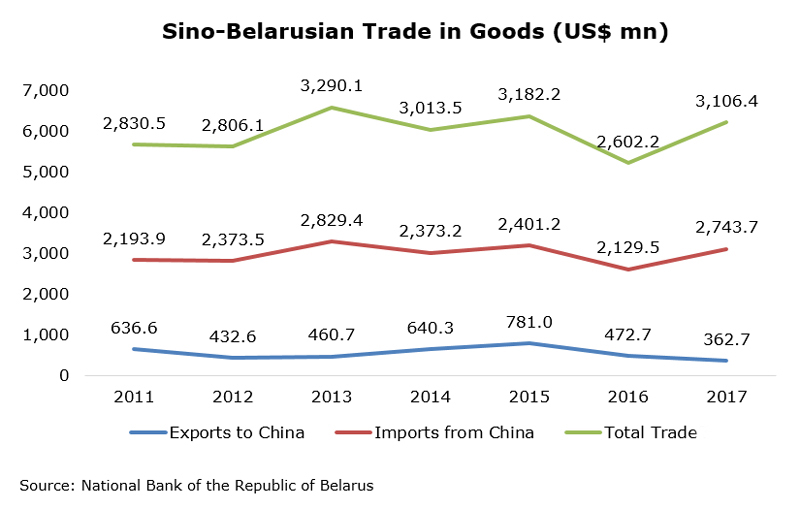

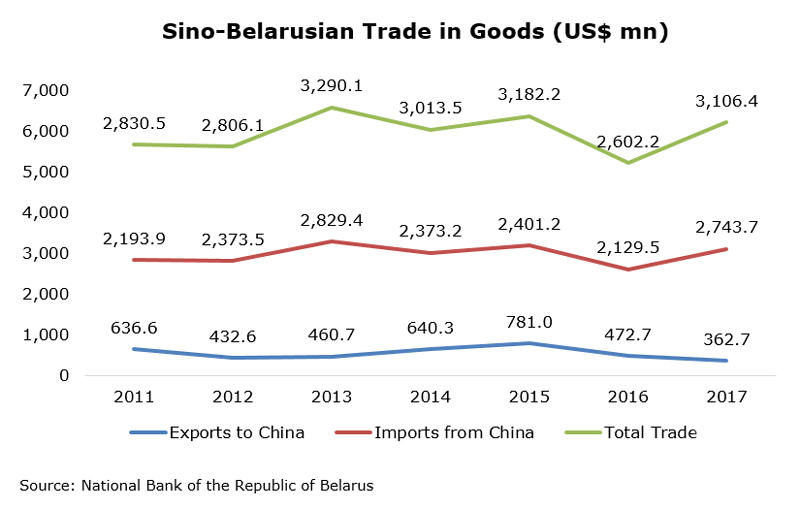

On the trade front, China is Belarus’ third largest trading partner (after Russia and the EU) though it only bought 1.2% of Belarusian exports and supplied 8% of Belarusian imports in 2017. Last year, China was Belarus’s sixth most important export destination (after Russia, the EU, Ukraine, Kazakhstan and Brazil) and third most important import source (after Russia and the EU).

With a strong agriculture and livestock sectors, expansion of agricultural trade such as sugar beet, vegetables, potatoes, grains and legumes, rapeseed, and flax fibre, along with meat and dairy industry exports, has always been one of the focal points of the country’s external trade development. To this end, Belarus and China signed a deal in July 2017 and became the first CIS country to export beef and poultry to China.

Source: The Press Service of the President of the Republic of Belarus

Following the deal signed between the two countries, the first shipment of frozen beef from Belarus arrived in the Chinese market in February 2018. A separate investment agreement concluded at the same time will soon see a Chinese food group building a livestock farm for 50,000 head of cattle in the Vitebsk Oblast, with a total investment of around US$400m.

While Belarus has a flourishing food and food processing industry, not every Belarusian product has received the go ahead to be sold in the Chinese market. Hong Kong, as a free port, can act as a test bed to promote and distribute Belarusian agricultural and dairy products in other key Asian markets. Some of the first movers include the seven Belarusian companies[3], which debuted some of the country’s traditional delicacies and drinks such as confectionary, pastry, natural juices and 68% vodka at the Hong Kong Food Expo 2017.

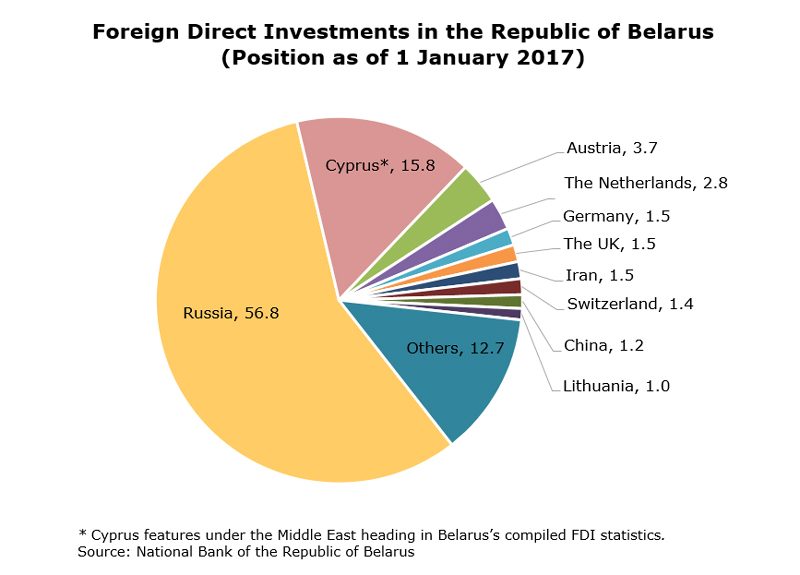

European countries, such as Russia, and several EU member states like Austria, the Netherlands, Germany and the UK, dominated Belarus’s FDI scene as they did on the trade front, contributing nearly 75% of the country’s FDI as of 1 January 2017. But China, despite its small share of only 1.2% (i.e. US$231.8mn) of the total, was already the largest Asian investor in Belarus, while Hong Kong came fourth behind South Korea and Singapore, with a FDI position of US$3.8mn.

While China is currently far from being able to challenge the position of Russia and the EU in terms of trade with and investment in Belarus, there is clearly room for expansion. This fits in with China’s BRI vision and the Belarusian government’s desire for public-private partnerships (PPPs) as a means of implementing several forthcoming infrastructure projects.

Prospective projects include the M-10 Highway Reconstruction, the country’s pilot PPP project, which involves a two-year construction period and an 18-year operational period. It is being built in collaboration with European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD). Also of interest to Chinese and Asian investors are the development plans for Belarus’s secondary towns and rural areas, including 100 settlements with fewer than 60,000 inhabitants. In that regard, China has already had a hand in two state housing projects.

Examples of PPP Projects in Republic of Belarus

| Name of project | The initiator of the project | Preliminary cost of capital expenditures | The current stage of preparation |

| Reconstruction of the M-10 highway: the border of the Russian Federation (Selishche) – Gomel – Kobrin; 109.9 km - 195.15 km | The Ministry of Transport and Communications | US$200mn | The feasibility study for the project is under preparation as part of the agreement between the Republic of Belarus represented by the Ministry of Transport and Communications and the EBRD. |

| Reconstruction of the complex of buildings of City Clinical Hospital No.3 in Grodno into Grodno Regional Clinical Oncology Centre | Grodno Regional Executive Committee | US$100mn | Negotiations are underway to attract the International Finance Corporation to finance the preparation of the project. |

| Construction of three children's preschool institutions in Minsk region | Minsk Regional Executive Committee | US$13.2mn | With the financial support of the EU, a selected consortium of consultants is developing a feasibility study for the project. |

| Designing and construction of the ambulance station in Baranovichi | Baranovichi District Executive Committee | US$4.3mn | Sources for preparation and subsequent implementation of the project are being searched. |

Source: National Agency of Investment and Privatization, Republic of Belarus

In terms of securing investment for large-scale infrastructure projects, Hong Kong’s status as an international financial centre makes it ideally equipped to broker Belarusian PPP projects and act as a useful partner when it comes to matchmaking Asian investors with substantial Belarusian infrastructure initiatives, especially after the great success of the Great Stone Industrial Park led by the Hong Kong-based CMG.

[1] Details of the EAEU’s Unified Customs Tariffs (UCT or CU) applicable on the goods imported from third countries can be found on the website of Eurasian Economic Commission.

[2] Belarus is the 160th country or territory having granted visa-free access or visa-on-arrival to HKSAR passport holders.

[3] The seven Belarusian companies are Krasny Pischevik, Spartak, Slodych and Kommunarka confectioneries, Minsk Kristall distillery, Brest Belaclo distillery and Krinitsa Brewery.

Editor's picks

Trending articles

By Michael Kugelman, Deputy Director of the Asia Program and Senior Associate for South Asia at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars

Executive Summary

This essay assesses the scale and energy dimensions of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), identifies key obstacles, and discusses the implications for energy geopolitics.

Main Argument

CPEC has great potential to ease Pakistan’s energy supply shortages. It could conceivably zero out the country’s energy shortfall, which ranges from 5,000 to 7,000 megawatts (MW), and produce a more diversified and cheaper energy mix for a nation that currently depends on expensive local furnace oils and oil and gas imports. Initial CPEC power projects, comprising coal, gas, hydro, solar, and wind, are envisioned to generate over 27,000 MW. CPEC could also help China pursue its broader strategy of accessing far-flung energy and other markets. CPEC is one of the core land routes associated with China’s Belt and Road Initiative and involves some of the initiative’s first projects to be operationalized. However, it is also fraught with risks. These include Pakistan’s questionable ability to repay loans, as well as security threats posed by separatist insurgency, terrorism, and organized crime. For these reasons, CPEC’s future prospects remain uncertain.

Policy Implications

- CPEC may enable Pakistan to generate more power, but it will not solve the country’s broader energy crisis, which is rooted in factors that go well beyond supply shortages.

- Stability in Pakistan’s security situation and economic performance is an increasingly critical interest for Beijing because it is a precondition for CPEC’s success.

- Given New Delhi’s strenuous opposition, CPEC will exacerbate India-Pakistan tensions.

- CPEC cements the already deep presence of Washington’s top strategic competitor in a region where the U.S. has a much lighter footprint.

Please click to read the full report.

Editor's picks

Trending articles

By Michael Lundberg and Acacia Hosking

Developments in the growth of renewable energy are largely influenced by government policy. Subsequent changes in government policy to reduce state support of the renewable energy sector have led to a significant volume of investment arbitrations being initiated against states who have implemented such reforms in recent years.

These arbitrations typically involve claims, brought by investors, that a state has breached the fair and equitable treatment standard in relation to the investment and/or that the state expropriated the investment, through subsequent legislative or policy reform.

The European Commission’s 2009 renewable energy directive established an overall policy for the production and promotion of energy from renewable sources in the European Union, with a renewable energy target of at least 20% by 2020.

The directive recognised the need for national mechanisms supporting the promotion of renewable energy in order for EU member states to achieve their national targets. This led to an increase in European government incentive programs. These included fiscal incentives in production and consumption as well as incentives based on energy saving instruments that raise efficiency in energy-intensive sectors through information and communication technologies.

Programs and policies encouraging investment and the production of renewable energy in countries including Spain, Italy, the Czech Republic and Canada have resulted in increased investment and electricity generation. Such programs predominately target renewable resources such as wind and solar energy.

There are increasingly less government incentive renewable energy programs. However, cost reductions in new renewables technology have eliminated the need for such incentives and consequently, renewable energy remains a sector focus.

Governments continue to announce and implement renewable energy goals and mandates, most recently with Taiwan announcing an ambitious target of reaching 20% renewable energy by 2025 mirroring the targets set by the EU. The scale of continued investment and growth in renewable energy production will inevitably lead to further disputes, and see new developments in investor state disputes.

Energy Charter Treaty

The majority of investment arbitrations initiated against EU member states have been brought pursuant to the Energy Charter Treaty (ECT). The ECT is a multilateral treaty which was signed in 1994 and came into effect in 1998, intended to facilitate investment in and the development of the energy sector. All EU member states except Poland and (since 2015) Italy are signatories to the ECT. Relevantly, Article 10 provides (inter alia) for fair and equitable treatment of investors, while Article 13 prohibits expropriation.

Article 26 provides for alternative dispute resolution mechanisms, including international arbitration, with parties having the option to submit arbitral disputes to:

- the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID) (provided both parties are signatories to the Washington Convention);

- ICSID Additional Facility arbitration (if one party is a signatory to the Washington Convention but the other is not);

- ad hoc UNCITRAL arbitration; or

- arbitration administered by the Stockholm Chamber of Commerce (SCC).

The majority of disputes arising under the ECT have resulted in ICSID arbitrations.

In this article we set out some key developments in Europe and North America, in particular, Spain (under the ECT) and Canada (under NAFTA).

Case study – Spain

In 2004, the Spanish government began to introduce incentives to encourage investment and development in renewable energy which were expanded in 2007. The incentives included a feed-in- tariff (FIT) for a 25-year period, an entitlement for all energy generated to be distributed to the Spanish electricity grid and no limitation on the operating hours of electricity generation.

The Spanish government’s incentives resulted in exponential growth in Spain’s solar energy sector including around €50 billion of investment, which coincided with the Global Financial Crisis and culminated in an electricity tariff deficit (i.e. the difference between the regulated tariff collection and the associated real costs) of circa €35 billion by 2012.

To address the deficit, from 2010 onwards the Spanish government began to implement policy changes including ceasing the premium price guarantee after the 26th year of the solar plant’s operation, requiring certain plants to install mechanisms to protect the electricity grid from voltage dips, limiting operating hours and implementing a new charge for grid access.

Further changes in 2013 resulted in the incentives being eliminated entirely and a new regime was introduced which was much less generous than the previous one.

Around 30 investment treaty arbitrations have been filed against Spain as a result of its renewable energy sector reforms. The first award in these arbitrations was delivered in Charanne BV and Construction Investments SARL v The Kingdom of Spain, a SCC arbitration brought against Spain under the ECT by a Dutch company and a Luxembourg company which had jointly invested in Spanish solar energy generation.

The claimants contended that the reforms by the Spanish government breached Articles 10 and 13 of the ECT by violating the standard of fair and equitable treatment, denying their legitimate expectations as investors and reducing their return and expropriating part of the value of their investment.

In January 2016, the majority of the Tribunal dismissed all claims against the Spanish government. Spain’s reforms of the renewable energy subsidies were found not to breach the claimants’ legitimate expectations under the fair and equitable treatment provisions of the ECT.

To exercise the right of legitimate expectations the Tribunal held that the claimants must show that they had first made a diligent analysis of the legal framework for the investment. The materials provided to the investors in 2007 did not state that the FIT would remain in place for the regulatory lives of the solar plants. A commitment to a group of investors did not amount to a commitment to an individual investor and to find otherwise would amount to an excessive limitation on the power of the state to regulate the economy in accordance with the public interest.

The expropriation claim was dismissed on the basis that the claimants had failed to demonstrate that they had been deprived of all or part of their investment, in circumstances where the incentive program and the associated contracts remained in place, albeit with a reduced rate of return. The dissenting arbitrator was of the view that legitimate expectations can arise where states grant incentives to a specific category of persons in exchange for their investment.

The scope of the Spanish government’s reform the subject of Charanne was relatively minor, as it was limited to the 2010 amendments. The reforms to the Spanish renewable energy incentives in 2013 were far more substantive with purported retroactive application.

Therefore, while the majority of claims brought against Spain under the ECT were similarly founded on the contention that Spain’s reforms to government incentive programs breached the investor’s legitimate expectations under the fair and equitable treatment provisions of the ECT, most of the pending claims concern the subsequent and more far reaching reforms than those the subject of Charanne.

In May 2017, an ICSID Tribunal delivered the first award which considers the subsequent Spanish reforms in Eiser Infrastructure Limited and Energia Solar Luxembourg v Kingdom of Spain, ICSID Case No. ARB/13/36. In a unanimous award, the Tribunal ordered Spain to pay €128 million to the claimants, finding that the Spanish government had breached Article 10 of the ECT, depriving the claimants of fair and equitable treatment. The award is likely to impact the substantial number of investor state disputes still pending against Spain.

There are also a small number of energy and resources investor state claims brought against other European states including Italy, the Czech Republic, Croatia (concerning changes to its regulatory regime which effected a Dutch company’s investment in a biomass power plant), Bulgaria, Romania and Poland (noting that Poland is not a signatory to the ECT).

Case study – Canada

In 2016, awards were delivered in both Mesa Power Group, LLC v. Government of Canada and Windstream Energy LLC v. Government of Canada. Both cases concerned claims made pursuant to the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), regarding amendments to renewable energy incentive programs in the province of Ontario.

In October 2009, the Ontario government launched a FIT program which included 20 or 40 year power purchase agreements with the Ontario Power Authority (OPA) for projects that generated electricity exclusively from renewable energy. Those agreements provided a guaranteed fixed price for electricity delivered to the Ontario grid.

The Ontario government subsequently sought to cancel some of these programs, leading to investor state NAFTA claims.

In Windstream Energy, the Tribunal ultimately found in the claimant’s favour, awarding C$26 million. The proceedings arose out of a transaction in May 2010, when American company Windstream and the OPA entered into a FIT contract under which OPA was to pay Windstream a fixed price for wind generated power, with a total contractual value of C$5.2 billion.

In February 2011, following a policy review to develop the regulatory framework for offshore wind projects, Ontario decided to suspend all offshore wind development until further research was completed. Windstream commenced its arbitration against Canada, bringing a number of claims under NAFTA. As previously mentioned, windstream succeeded in its breach of Article 1105(1) claim, which provides for fair and equitable treatment and full protection and security in respect of a party’s investments (analogous to a breach of Article 10 of the ETC).

Mesa Power also involved a claim under Article 1105 but resulted in a very different outcome from the Tribunal. Mesa Power’s claims were dismissed and it was ordered to bear the cost of the arbitration, together with C$3 million of Canada’s legal costs.

Mesa Power had submitted several applications under the Ontario FIT program, but was unsuccessful in gaining a contract, allegedly due to inability to transmit electricity to the Ontario grid. In its claim against Canada, Mesa Power argued that its inability to acquire transmission access to deliver electricity to the Ontario grid was due to flaws in the contracting process and preferences granted to two other parties, contending that this conduct constituted a breach of Article 1105(1).

The increase in investment treaty arbitrations against states in the renewable energy sector is perhaps indicative of a wider trend where investors are now viewing investor-state arbitration as a legitimate dispute resolution mechanism, which does not necessarily preclude a continuing commercial relationship with the respondent state.

Where to from here?

Reductions to government incentive programs in the renewable energy sector in Europe have led to other markets leading the charge in the development of renewable energy. For example, the solar installation rate in the US doubled between 2015 and 2016, with 15,000 megawatts being installed in 2016.

These developments in the US have primarily been driven by solar investment tax credits, rather than FIT contracts, which have been relatively stable since their introduction in 2006. Outside of Europe and North America, the Taiwanese government recently introduced a target of 20% renewable energy by 2025. While admirable, the target is perhaps ambitious, given Taiwan’s current 5% renewable energy share and its goal of requiring US$59 billion of private capital to achieve its target (in addition to the already substantial US$41 billion to be invested by the government).

As investment increases, projects develop, and states continue to pursue their renewable energy targets, emissions targets and other plans to reduce or eliminate non-renewable energy production, it is inevitable that renewable energy related arbitrations will continue to emerge.

Please click to read full report.

Editor's picks

Trending articles

AliExpress logistics centre set to be built close to country's border with Germany as overall e-commerce levels soar.

Poland is set to be the site of major new AliExpress logistics centre, serving its host country as well as online shoppers in neighbouring Germany and the Czech Republic. The new centre is to be a joint venture between the Alibaba-owned online marketplace, the Shanghai-headquartered Worldwide Logistics Group (WWL) and ATC Cargo, a multi-modal Polish freight delivery company.

The move is seen as recognition of AliExpress' success in building its customer base in eastern and central Europe. Although Allegro – Poland's take on eBay – remains the most popular e-commece site in the new centre's host country, the Chinese online platform has made huge strides in terms of building market share and consumer awareness. As a sign of this, in an October 2017 survey conducted by PayU, the Dutch fintech company, AliExpress was namechecked by 62% of Poland's online shoppers when they were asked to identify e-commerce market leaders.

Another factor in the choice of Poland as the site of the new centre is its strategic geographical advantage with regard to the aims of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), China's ambitious international infrastructure development and trade facilitation programme. This would see Poland function as the primary land conduit between China and the mega-markets of Europe, particularly Germany's 81-million strong consumer base. As a wider acknowledgement of the country's geographical advantages, Amazon has already begun work on its own US$876 million logistics facility in Szczecin, a city in northwest Poland set close to the German border.

One of the advantages of the new AliExpress facility is that, for the first time, it will allow businesses in the region to buy goods in small batches rather than by the container-load, as has been the previous practice. It will also help to manage the increased traffic between China and Poland, with some 500,000 parcels handled in 2017, a 200% increase on the previous year.

One negative aspect of this increased throughput, however, is that the huge surge in the volume of trade has spurred moves by the Polish government to clamp down on VAT avoidance on the part of the country's e-shoppers. Poland, unlike most other European countries (with the exception of France), does not waive the duty on imported e-commerce items valued at up to $55. To date, though, the Polish treasury has taken no action to enforce payment on such items.

In light of the increasingly large sums involved, however, actions are now being taken to ensure that such payments are processed. The most likely solution will see buyers permitted to specify the value of each delivery online, with the government's own system verifying this with the relevant e-commerce platform.

● In other moves, the Polish Financial Supervision Authority (KNF) has now signed a fintech cooperation agreement with the Hong Kong Monetary Authority (HKMA). This will see the two bodies working together on a range of fintech-related research projects, while also facilitating a wider exchange of information, mutual consultation and a greater overall level of knowledge and expertise interchange.

Anna Dowgiallo, Warsaw Consultant

Editor's picks

Trending articles

By CIGI Graduate Fellows, Balsillie School of International Affairs

Potential Opportunities for Canada?

A policy brief recently published by the Balsillie School of International Affairs in Waterloo Canada reports that in a survey by the Canada China Business Council, 74 percent of respondents were aware of the BRI, and 44 percent of respondents see opportunities available for them within the BRI (Kutulakos et al. 2017, 41). This same survey outlines respondent-identified opportunities with the BRI, including:

“Using Chinese distribution network to spread Canadian products through Chinese hubs.

- Explore opportunities in Northwestern part of China where Canadian products still have large room to grow from agriculture technologies to clean energy.

- It might help decrease the fees related to exporting [Canadian] products.

- Cross-border investment work between China and other [BRI] countries.

- Infrastructure

- Technology

- Services

- [Canada is] a provider of minerals and products that will be essential to construct the One Belt One Road infrastructure.

- More business activities in [British Columbia] with China, as Pacific Gateway of China to North and South Americas.

- Satellite communications networks are key infrastructural elements of their build out.

- Providing specialised technologies and services for infrastructure development.

- Environment protection around the Silk Road area.” (ibid.)

The policy brief, by Michael Fleet, notes that beyond business opportunities, the BRI provides Canada with a means to become better connected economically, as well as politically, through increased interactions with BRI states. As Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) states such as Singapore look to increasing their infrastructure capacity through the BRI (BDO Singapore 2015), Canadian infrastructure and engineering expertise can assist in obtaining contracts in the region. Furthermore, several European states, and the European Union (EU) itself, are looking to become potentially involved with various projects with the BRI; as Canada enters into a free trade agreement with the EU, BRI projects may provide opportunities for Canadian businesses to cooperate with EU businesses. Although the United States is currently Canada’s leading trading partner, it is critically important to pay attention to the potential for economic growth in Asia, as it will overtake the United States as the fastest growing centre of global trade. Canada needs to diversify its trading partners and establish its presence in Asia to further connect its economy and relations to other global partners.

Effective policy making can nurture Canadian small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) for global scalability and the BRI opens doors for many Canadian businesses. Through a careful tuning of already existing policies and funds, such as the Innovative Solutions Canada fund and the Venture Capital Action Plan, the Canadian government can work with SMEs to assist with global scalability (Bergen 2017). Examples such as Bombardier Inc.’s announcement in 2016 of building 80 high-speed trains for Turkey, as well as a CDN$100 million technology transfer investment in Turkey’s high-speed network, are illustrative of opportunities presented by the BRI (Kirkham 2016). Indeed, Bombardier Inc. is already looking to grow (Lampert 2017), and the increased demand for infrastructure projects within BRI is most opportune.

Canada is currently involved in several economic initiatives in the region: from free trade agreement talks with China and India, to the Asian Development Bank and the AIIB. But beyond its dealings with China, Canada is also interested in advancing its economic goals in Southeast Asia, and involvement in BRI projects could signal Canada’s commitment to further relations with ASEAN member states. A key Canadian objective is to become a member of the ASEAN Defence Ministers Meeting plus (ADMM+). The ADMM+ is of Canadian interest as it allows Canada to have a voice in watching how relevant states interact concerning the ruling from The Hague on the South China Sea.

Recommendations

Lobby in the AIIB for a fair tendering process in contracts for Canadian companies with the BRI, as well as push for a more transparent and sustainability aware tendering process.

Encourage Canadian businesses’ competitive advantage in fields such as transportation services and its engineering skills in BRI projects, which will allow Canadian companies the business opportunities and access to capital financing from groups such as the AIIB to scale up globally. Canadian initiatives such as the Innovative Solutions Canada fund and the Venture Capital Action Plan can help SMEs grow and gain access to both capital and customers on the global market, with the BRI as a source of projects. Furthermore, by becoming involved in the BRI’s early stages, Canadian companies can build relationships to obtain more contracts in the future. Canada should also do a thorough assessment of the vulnerability of its different economic sectors, and learn from its domestic assessments from the current China–Canada free trade agreement.

Integrate BRI business projects with Canadian development aid with entities like the Asian Development Bank in relevant states to develop a supporting role between infrastructure development with the BRI and environmentally sustainable programs, development of the clean energy industry, social infrastructure and maximization of poverty reduction. This approach would also align with Canada’s commitment to the Paris Climate Agreement and the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, an important marker for Canada’s objectives in obtaining a Security Council seat in the United Nations.

Establish further connections with relevant states and increased dialogue with China through embassies and missions, as well as through non-governmental organizations and businesses to explore further opportunities with the BRI and establish greater security and risk-evaluation sharing. This will increase people-to-people relations at various levels for increased Canadian presence in the region. As Canada and China expand their economic dialogue, Canada should further its presence with partners in the region through track one and track 1.5 diplomacy.

Geo-strategically, Canada must continue to seek a seat at the ADMM+. By working with the BRI and consulting with relevant states on a political and business level, Canada can begin building stronger relationships with partners in the region to assure its commitment and presence, which will assist in its application to the ADMM+. Here, Canada can lend its voice to the security of the South China Sea while monitoring the precedent-setting rulings of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, which are important considering the Canadian North and potential legal issues in the future. As arctic ice recedes from climate change, more routes will become accessible. The result will be more shipping moving through these waters in the Canadian north. Being able to watch and promote law-abiding norms for UNCLOS will help to ensure legal passage and rules for these new routes in the Canadian north.

Please click to read the full report.

Editor's picks

Trending articles

By Wu Qing, Monique Carroll and Josephine Lao

In the context of global warming, facing national pressure for energy conservation, emission reduction and haze management, China has adopted a policy agenda for energy structure optimisation and clean energy development. Clean energy refers to energy which produces very little or no pollutant. It includes renewable energy, such as solar energy, hydro energy, wind energy, geothermal energy, marine energy and a few fossil fuels like natural gas and clean oil.

China has abundant, though under-developed and inadequately utilised clean energy reserves. During the 13th Five-Year Plan period, a large number of clean energy power generation projects are expected to be approved and launched. Further, the acceleration of China’s clean energy vehicle industry means that there is a huge demand for charging infrastructure.

This article discusses investment opportunities in connection with these clean energy projects, and the associated environmental compliance risks.

Investment opportunities

The 13th Five-Year Plan period provides substantial policies in favour of and financial support for clean energy power generation, especially nuclear power, hydropower generation, and clean energy vehicle charging infrastructure construction projects.

Among China’s clean energy power generation projects, wind power and photovoltaic power generation are still restrained by their distinct intermittency and volatility, causing low returns. In comparison, nuclear power and hydropower generation projects are relatively mature, enjoying lower generation costs and higher utility.

Hydropower generation projects

China’s 13th Five-Year Plan period promotes the construction of hydropower stations. Nationwide, the newly built conventional hydropower stations and pumped-storage power stations currently provide 60 million kilowatts of power capacity. It is expected that in 2020 conventional hydropower stations will reach a scale of 340 million kilowatts, with the total installed capacity of hydropower reaching 380 million kilowatts.

China’s hydropower generation projects, with installed capacity exceeding 1 million kilowatts, qualify for tax credits in the form of rebates of value-added tax (VAT) paid.

Nuclear power projects

China is also launching a batch of advanced third generation pressurised water reactor nuclear power projects. The goal for 2020 is that the installed capacity of running nuclear power reaches 58 million kilowatts, and that the installed capacity of nuclear power under construction reaches 30 million kilowatts or higher.

The nuclear power industry also enjoys a series of tax incentives. First, nuclear power generation enterprises producing and selling electric power products are entitled to apply for VAT rebates within a period of 15 years. Any VAT refunded to nuclear power generators is income tax exempt but must be used for the repayment of principal and interest on finance. In addition, the Ministry of Finance and State Administration of Taxation have implemented preferential urban land use tax policies regarding land used by nuclear power stations.

Energy vehicle charging infrastructure construction projects

The 13th Five-Year Plan period also transitions China’s clean energy vehicle industry from infancy to advanced implementation. The government has set a target for the industry: production and sales in 2020 shall be more than 2 million while the cumulative production and sales shall reach more than 5 million. However, it has been difficult for China to promote clean energy vehicles due to the lack of charging infrastructure. Given this situation, the National Development and Reform Commission set up a five-year development target for the construction of charging infrastructure requiring 12,000 centralized charging and swapping stations and 4.8 million dispersed charging piles to be constructed by 2000.

To encourage this, the Chinese government provides subsidies to provincial/municipal/district governments where charging infrastructure meets local demands, and where clean energy vehicles are relatively well promoted and widely used. The state encourages local governments to apply the Public-Private Partnership model in such projects.

The 2017 newly revised Catalogue of Industries for Guiding Foreign Investment encourages foreign investment in clean energy power generation equipment, clean energy vehicles, hydropower stations for the primary purpose of power generation and nuclear power stations. However, in industries like manufacturing of whole automobiles and special cars, construction and operation of nuclear power stations and grids, it either requires Chinese parties to be controlling shareholders or sets certain bottom line proportion of Chinese investment.

Environmental compliance regime

Throughout the pre-construction project initiation and environmental impact assessment (EIA) phase, the construction phase, and finally, the post-construction operational phase, projects confront supervision by the departments of environmental protection, water administration, forestry, land and resources, and housing and urban-rural development.

Pre-Construction

Before construction commences, clean energy projects require a number of approvals. Projects are required to obtain a pre-examination opinion on the land used prior to the commencement of construction, which is issued by China’s land and resources authorities. Hydropower generation projects also require written consent from the relevant department on the project’s flood control plans prior to construction. Construction entities must also prepare a report, a report form or a registration form (the specific type depends on severity) outlining the environmental impacts of the project and must not commence construction before obtaining the EIA’s official reply. For construction projects that require a report of environmental impacts, if the construction entity did not seek the opinion of relevant entities, experts and the general public by holding demonstration meetings, hearings or by any other means, the construction employer could be ordered to solicit public opinions, or the previous EIA official reply could be annulled.

Construction

There are five main legal risks once construction has commenced:

- construction without EIA approval;

- drawing water without the appropriate licence;

- discharging pollutants without lawfully obtaining a pollutant discharge license;

- resources and ecological conservation and social problems; and

- division of environmental responsibility between construction contractors and construction project owners.

Construction without EIA approval

Any of the following situations could constitute construction without EIA approval:

- where any construction employer fails to submit the environmental impact assessment documents for its construction project;

- where any construction employer commences construction without permission before the environmental impact assessment documents are approved;

- where any construction entity fails to renew and resubmit clean environmental impact appraisal for examination and approval, if either the nature, scale, venue or production techniques employed, or the measures for preventing pollution and ecological damage has undergone substantial changes after the original application had been approved.

Construction without EIA approval can lead to disciplinary action against those directly responsible and liable persons, and also result in orders to cease construction, a fine of not less than 1% but not more than 5% of the total investment of the construction project, and orders to restore the site to its original state. For example, on 24 February 2015, the Environmental Protection Department of Qinghai Province imposed an administrative fine of ¥200,000 on the Qinghai Yellow River Upstream Hydropower Development Co., Ltd. for commencing construction of its Yangqu hydropower station project without permission before the environmental impact assessment documents were approved.

Water drawing license

Nuclear power and hydropower generation construction projects require a license to draw water. Failure to obtain the appropriate license, or comply with its conditions, can result in an order to stop illegal acts, a fine or a revocation of the license.

Pollutant discharge license

Enterprises and public institutions discharging industrial waste, gases or industrial waste water, directly or indirectly, must obtain a pollutant discharge license. Failure to obtain an atmosphere license could result in:

- an order to take corrective actions;

- an order to restrict production or suspend production for rectifications;

- an order to suspend business operations or close down;

- a fine; and/or

- administrative detention of directly responsible and liable persons.

Resources and ecological conservation and social responsibility

Matters like protection of woodland, watercourses, arable land and natural reserves should also be taken into account. For example, between July and September in 2016, the Forestry Bureau of Qijiang District imposed fines on Sichuan Qaingbo Electric Power Engineering CO., LTD for its requisition of woodland for expansion of its Anwen power plant without lawfully obtaining a woodland requisition license11. The requirements for each project must be considered on a case-by-case basis. For example, regarding hydropower station construction projects, emphasis should be placed on ecological conservation and resettlement of migrants, while security issues should be central to nuclear power station construction projects.

Ongoing environmental responsibility – construction contractors and construction project owners

While construction is underway, responsibility for environmental risk should be clearly divided between contractors and project owners. The issues regulated include the prevention and control of dust pollution, clearance and treatment of solid wastes, and construction noise. There are different criteria to divide responsibility between contractors and project owners for each environmental risk.

Post-Construction

During the operational phase, major environmental problems that hydropower generation projects may encounter lie in water pollution, ecological water discharge and treatment of hazardous wastes. For nuclear power generation projects, dealing with radioactive pollution and water pollution is the most important. As for clean energy vehicle charging infrastructure, risks include leakage of electricity and fire.

In each phase, if substantial requirements are not met, the relevant approval may not be obtained. To manage these risks, internal compliance departments could undertake a project environmental risk assessment early on and engage with the agencies which might be involved to provide professional advice on risk assessment and control.

Summary

China’s clean energy projects enjoy promising investment prospects during the 13th Five-Year Plan period. Among them, nuclear power and hydropower generation projects have relatively solid foundations, which makes them a wise investment choice.

Further, given China’s current push to develop clean energy vehicles, clean energy vehicle charging infrastructure construction projects have great room for development. However, foreign investors need be aware of and plan for environmental legal risks in the pre-construction, construction and post-construction phases of clean energy projects.

Please click to read full report.

Editor's picks

Trending articles

By Evelyn Goh, ANU and James Reilly, University of Sydney

As the dust settles from the Chinese Communist Party’s 19th Congress, one of the strongest edifices left standing is Xi Jinping’s signature foreign policy initiative — the US$1 trillion Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Two members of the BRI Leading Small Group, Wang Hunning and Wang Yang, secured five-year positions on the reshuffled Politburo Standing Committee. The BRI even received an awkward mention in the revised Party Constitution.

The BRI generates political influence through ‘connectivity power’ — the influence a central government accrues through infrastructure projects that connect its domestic periphery and neighboring states to the central core economy. Three types of infrastructure projects are most likely to generate connectivity power: transportation (roads, railways and ports), communication (cellular networks and internet cables) and energy (oil and gas pipelines, hydropower dams as well as electrical lines and grids).

Within these projects, China’s connectivity power is likely to emerge through four mechanisms.

First, and most directly, new infrastructure projects should bolster the flow of people, goods, capital and energy. Since the BRI is essentially a promise for a US$1 trillion state-backed investment surge, capital flows in particular are likely to yield an ‘early harvest’.

The BRI already appears to be stimulating additional investment, as more Chinese investors take a stake in firms in BRI recipient countries, perhaps in the expectation that they will receive easier access to BRI-earmarked capital or can capitalise upon Beijing’s efforts to boost exports from BRI-recipient countries. By August 2017, the value of Chinese mergers and acquisitions in the 68 countries officially participating in the BRI already totalled US$33 billion, surpassing the US$31 billion tally for all of 2016.

Trade patterns are less likely to change dramatically, since China already represents the most important source of imports for about three quarters of BRI countries and is the most important trading partner for just under half of them. Yet even in trade the BRI’s impact is emerging. China’s trade with BRI countries in the first half of 2017 rose four per cent faster than China’s overall foreign trade. Standouts include Russia, Pakistan, Poland and Kazakhstan — all key players along the new Silk Road.

As new energy projects come on line they will also begin to reshape energy flows. For instance, the Kyaukphyu–Kunming natural gas and oil pipelines across Myanmar and into Yunnan province enable Beijing both to diversify its energy sources and to tighten economic interdependence with Naypyidaw.

Second, connectivity projects help put China at the centre of a thickening web of linkages, bolstering Beijing’s capacity to set the standards by which trans-border networks operate. China’s high-speed trains and ultra-high voltage electrical lines, for instance, will likely shape regional standards as they begin to stretch beyond China’s borders.

In China’s bid for global influence, currency may well be the most significant standard it can aim to reset. Over half of the 35 economies that have signed currency deals with China are in the BRI. Of the 68 BRI countries, one third now have direct access to the Chinese renminbi (RMB) from their own banks. Economists confirm that easy access to the RMB promotes trade with China. Mongolia is a prime example. Almost 90 per cent of its exports go to and one third of its imports come from China. In 2014, Ulaanbataar signed a 15 billion RMB (US$2.2 billion) currency swap agreement with China, which was extended for another three years in July 2017.

Connectivity power can also extend into institutions. Established multilateral development institutions, such as the Asian Development Bank, may incorporate Chinese-backed projects. For instance, the World Bank funded the Kazakhstan stretch of the Western Europe–Western China Highway, which will now serve as the main roadway of the BRI’s central corridor. But such synergy can cut both ways — the involvement of Western financial institutions might dilute Beijing’s influence over the terms of lending, or they may help legitimise and amplify China’s model of infrastructure-led development.

A fourth pathway of potential influence runs through the domestic politics of recipient countries. Beijing hopes that domestic groups benefitting from the infrastructure projects will lobby on China’s behalf. Greece’s influential shipping industry, for instance, has quietly nudged Athens toward a non-confrontational China policy following massive Chinese investment into Greece’s shipping sector.

Like any ambitious policy initiative, Xi Jinping’s BRI strategy entails considerable risk. Beijing-backed infrastructure projects can alienate influential groups and trigger populist backlash, pushing leaders to adopt anti-Chinese rhetoric.

Further, while extending massive loans may initially bolster Beijing’s influence, leverage shifts to the host country once the project is underway, as was starkly evident in the case of the Myitsone Dam in Myanmar. Since Myanmar’s leadership bowed to public pressure and froze the massive project in 2011, Chinese investors and officials have been unable to compel a policy reversal or even secure compensation.

Increased connectivity also facilitates factors of instability. Guns and drugs are smuggled into China through burgeoning trade routes. Beijing has long been wary of engagement between its Muslim-dominated provinces — Xinjiang and Ningxia — and the Muslim world in Central Asia and the Middle East due to fears of importing instability.

As Deng Xiaoping warned decades ago, ‘when you open the window, a few flies will come in’. Like Deng, Xi Jinping appears eager to take this risk.

Please click to read full report.

Editor's picks

Trending articles

US$1.7 billion of Chinese backing set to deliver Karnaphuli Tunnel Project, a key Belt and Road component.

Construction work on the China-backed Karnaphuli Multi-Channel Tunnel Project in southern Bangladesh is now well under way. The tunnel is seen as a key component in several projects related to the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), China's ambitious international infrastructure development and trade facilitation programme. Once completed, the tunnel will connect the port city of Chittagong to the far side of the Karnaphuli river, the site of a new Chinese economic zone.

Due to be completed in 2020, the tunnel will slash the travel time between Chittagong and Cox's Bazar, one of the country's leading tourist destinations, and ease the heavy congestion on the existing two bridges across the river, while also connecting-up with the Korean Export Processing Zone and Shah Amanat International Airport. It will also feed into two other projects that are currently under way – the Asian Highway and the Dhaka-Chittagong-Cox's Bazar Highway.

At present, it looks as if all of the required funding for the tunnel is now in place. According to government sources, US$1.02 billion of initial backing was secured from the China Exim Bank, with a further $663 million facility – repayable over 20 years at an interest rate of 2% – subsequently confirmed. The outstanding balance was then provided by the Bangladesh government.

The project has been jointly managed by the Bangladesh Bridge Authority (BBA) and the China Communication Construction Company, with the Hong Kong branch of Ove Arup & Partners providing additional design and technical support. With a total length of 9km – of which 3.4km will run below the river – it will be the first tunnel in Bangladesh to facilitate simultaneous road and rail transit.

The tunnel is just one of a range of China-backed projects currently underway in the region. Foremost among these is the Special Chinese Economic Zone – formally known as the Anwara 2 Economic Zone – which was officially established in June last year following the signing of a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) between the Bangladesh Economic Zones Authority (BEZA) and the China Harbour Engineering Company (CHEC).

According to Paban Chowdhury, BEZA's Executive Chairman, the zone will have the capacity to house 150-200 industrial units and will focus on a range of different industrial sectors, including shipbuilding, pharmaceuticals, electronics, agro-business, IT, chemicals, power and textiles. With up to 75,000 jobs set to be created, the zone will not exclusively rely on Chinese businesses, with Chowdhury saying: "As per our initial agreement, while Chinese investors will get preferential treatment, other local and overseas businesses will also be welcome."

In the case of both the tunnel and the economic zone, their success is heavily reliant on the Chittagong port's facilities being substantially upgraded. The port currently handles a staggering 92% of Bangladesh's ocean freight, with the country's surging economy seeing the required throughput growing by about 14% a year.

The port, however, is heavily silted and extremely congested, while also lacking the depth required for the current generation of tankers. As a result, it is widely accepted that a deep-water port upgrade is a priority for the country.

Over recent years, though, attempts to implement such an upgrade have fallen foul of a series of international disagreements. Back in 2010, China agreed to put up the money for the port's expansion, as well as for the development of a deep-water port on the nearby Sonadia island. Then, in February 2016, in something of an abrupt about-turn, the project was scrapped in favour of a Japanese-funded port development at nearby Matarbari, the proposed site of a massive coal-fired power station.

Such wrangling, however, has not lessened Bangladesh's strategic significance to the overall BRI project. The country is a key component of the proposed Bangladesh-China-India-Myanmar corridor (BCIM), one of the programme's six priority routes.

Overall, Bangladesh is also seen as a vital conduit between the semi-industrialised ASEAN countries and the highly populated Indian sub-continent. Its strategic location between South Asia and Southeast Asia also makes it an essential link in the BRI's mission of trans-regional integration.

Geoff de Freitas, Special Correspondent, Dhaka

Editor's picks

Trending articles

With the Lower Sesan Two Dam just the latest Cambodian beneficiary of BRI funding, further collaborations await.

As the waters of the Lower Sesan Two Dam began to rise last month, it marked the completion of just one of the many Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) projects currently underway in Cambodia. While China and Cambodia have a long history of co-operation, the BRI – the mainland's ambitious infrastructure development and trade facilitation programme – has taken this to new heights, particularly with regard to power generation.

Sesan Two is just the latest in a series of hydropower projects, largely built in collaboration with China, that have transformed Cambodia's energy landscape. The country has long suffered from a severe electricity shortage and, with its power generation largely fueled by diesel oil, its per watt prices have been among the world's highest. With its booming manufacturing economy sending demand growing by 18% a year, a large-scale hydropower development plan was seen as a priority as far back as 2003.

Even in those pre BRI-days, China recognised the strategic importance of nurturing the economic development of its near-neighbour. As a consequence, mainland businesses have long-bankrolled the development of Cambodia's hydropower sector.

In 2006, Sinohydro invested about US$280 million in such projects, while Sinomach and China Gezhouba jointly provided funding of around $540 million in 2008, with Huadian Power adding in another $580 million in the same year. More recently, China Huaneng, via its HydroLancang subsidiary, injected $410 million into the Sesan Two project. The outstanding costs of this $977 million project were then jointly met by Vietnam's EVN International and the Royal Group, one of Cambodia's largest investment-oriented conglomerates.

At present, seven of the hydropower facilities already online feed into the country's national grid, with a further two installations servicing more local power requirements. By the end of the year, when it is fully-operational, Sesan Two will have an annual capacity of 400MW, making it the country's largest single hydropower source.

As a result of the programme, electricity generation has soared across the country, sending prices tumbling. In 2014, when the hydro plants of Stung Tatai (246MW) and Lower Stung Russei Chrum (338MW) plants came online, the country's total level of hydropower-sourced energy soared by 82%, rising from 1,015.54 million kWh in 2013 to 1,851.60 million kWh. Despite such massive steps forward, the hydropower programme is still seen as in its infancy, with many more installations planned.

Despite the clear benefits to the country in terms of more affordable and more readily-accessible power, the hydropower programme has not been without its critics. Indeed, the Mekong River Commission (MRC), a regional advisory body, has warned that any further expansion of the sector could actually impair Cambodia's economic development.

More specifically, the MRC sees further hydropower developments as likely to result in a 70% drop in lake and floodplain fisheries production across the Mekong basin areas. This, it says, could see Cambodia's GDP drop by between $3 billion and $5 billion for the period 2020-2040.

On top of such dire prognostications, others have maintained that the economic argument in favour of further hydropower development may actually be fundamentally flawed. In particular, the steady decline in solar power costs – a technology that has a far lower environmental impact – is seen as making it an increasingly viable alternative.

Perhaps sensing a likely change in national and international sentiment on this front, last December saw China's Hengtong Optic sign a $200 million BRI-related deal with the Inner Renewable Energy (Cambodia) Company. This will see the businesses jointly develop two solar-powered 100-MW generating plants.

Geoff de Freitas, Special Correspondent, Phnom Penh